Fast forward several thousand years to present-day Oxford. As the vast array of translated pieces at the ‘Babel: Adventures in Translation’ exhibition at the city’s great Weston Library attests, this “scattered, tribal, insular” vision of the future does not reflect how language development has actually played out in reality. Texts spanning hundreds, even thousands of years pay testament to the fact that communication has not ceased as a result of the multitude of languages spoken across our planet. Indeed, in many ways, this linguistic variation adds new layers to our ways of thinking, encouraging us to see our world through the eyes of people who would describe that very same world using an entirely different vocabulary. The fact that we can understand these texts is all thanks to the act of translation – the conversion of one language into another. Often, the act of translation goes unnoticed, but without it, our world would be a very different place.

Throughout history, humans have found new and innovative ways of communicating with each other, in spite – or perhaps more by virtue – of the diversity of their tongues. Fables, myths and legends have crossed borders and become firmly embedded in the collective cultures of people all over the world thanks to the translators who opened them up to new audiences and generations – translators who, it’s worth noting, made great efforts to learn the languages they were translating from in the first place. Starting with the Sanskrit animal tales of the Panchatantra of the fourth century BCE and Aesop’s famous Greek fables from the sixth century BCE and going right up to Beatrix Potter and the Disney-fied fairy-tales of the 21st century: translation has acted as the vehicle through which some of our favourite stories and morality tales have been preserved and passed on. The sheer number of languages Harry Potter – the most popular work of children’s fiction of our time – has been translated into perfectly demonstrates the power of language and imagination to traverse borders.

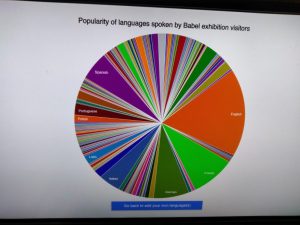

The Babel exhibition doesn’t just celebrate the work of translators in the dissemination of myths and legends. It also explores the very pertinent and all-too-often undervalued role of translation in today’s society, right here in the UK. From the bilingual signs lining the highways of Wales and the Japan-Cheltenham fusion that is the SuperDry brand, to the Italian restaurants and Polish delis that have become a staple of many a British high street: we live in a society that is increasingly being described as ‘globalised’. That is, a society that is open to and made up of international influences weaved into and layered on top of our own identity as a people and a nation in the form of cultural and linguistic borrowings. As the political Zeitgeist frequently and often tragically attests, acceptance of our situation as a nation of diversity is by no means complete. But that doesn’t make the situation any less of a reality. The ‘Negotiating multilingual Britain’ section of the exhibition addresses the popular perceptions of the British as less-than-enthusiastic language learners head on, stating that “The British are known for their lack of foreign language competence.” It also encourages us, though, to think about the many people living in Britain today who do use two, three, perhaps even half a dozen languages every single day to communicate with a whole range of people. Different languages might be used in the workplace, at school, at home, or in church. Translators, interpreters and others who possess more than one language are a crucial resource, but their skills often go unnoticed. As the exhibition itself attests, these often untapped or underappreciated language skills constitute “a national asset awaiting discovery”.

Perhaps the most striking part of the exhibition is its centrepiece: a spade encased in glass housing, surrounded on all sides by luminous green pellets. Visitors are asked to ponder how the important messages of today will be passed on to future generations. In this case, how will our descendants know not to unearth the nuclear waste we have buried deep underground? Will signs written in today’s main global languages be sufficient? How do we know that these languages will still exist in several thousands of years? Would symbols be any more effective if their meanings are lost over time? Should we create our own, modern-day fables to be passed down to our children and their children’s children as cautionary tales? The answers to these questions have not yet been found. But the role translation is set to have in facilitating this crucial transfer of knowledge is abundantly clear.

We all know that the dissemination of languages across the world, however it happened, has not in fact brought about a global cease-and-desist when it comes to communicating. International trade has not ground to a halt; travel is not limited by linguistic barriers; news travels around the world as fast as it does precisely because humans are able to make sense of each other, with technology undoubtedly providing an added boost. This is why I find it hard to reconcile the story of Babel with the idea of “punishment”. Ultimately, the “curse” apparently placed upon the seemingly impudent architects of the Tower of Babel translates to what we would understand today as “linguistic diversity”. To my mind, this diversity does not represent a barrier – it represents the possibility to explore, to make new friends, to learn new things and to have new experiences – and to understand that our mother tongue is not the only language in which we can have our best and brightest ideas.